The Whole Spiel

Claiming Space for Women

by Sarah Leavitt, Curator

March 20, 2024

Happy Women’s History Month! Designated in 1987, this “holiday” is even younger than the former Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington (incorporated 1965). Although, famously, women have always existed, the idea that historians and the general public should study the lives of women really hasn’t been around that long. As the daughter of a women’s history professor, I grew up with the assumption that women had a history; however, this seemingly obvious statement hasn’t always been an easy fact for historians (and museum curators) to swallow. Much historical scholarship and many museum exhibitions—including early ones put on by the Jewish Historical Society back in the day—have focused on the worlds of men—on governments, wars, and institutions led by men.

Luckily, we’re not there anymore. Women’s History has been a field at most colleges and universities for a half-century now. My mom’s colleague and dear friend Gerda Lerner (1920-2013) fled with her Jewish family from Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1939 and spent her career in the United States establishing the field of women’s history, helping to bring Women’s History Week to life in the 1970s. It took several more years for the week to become a month, finally established by the US Congress right here in Washington, DC, in 1987. The designation took longer than it should have!

So how is the Museum marking Women’s History Month?

"Screw the Patriarchy" corkscrew given to members of Congress by members of National Council of Jewish Women lobbying on The Hill, 2020. Capital Jewish Museum Collection. Gift of National Council of Jewish Women.

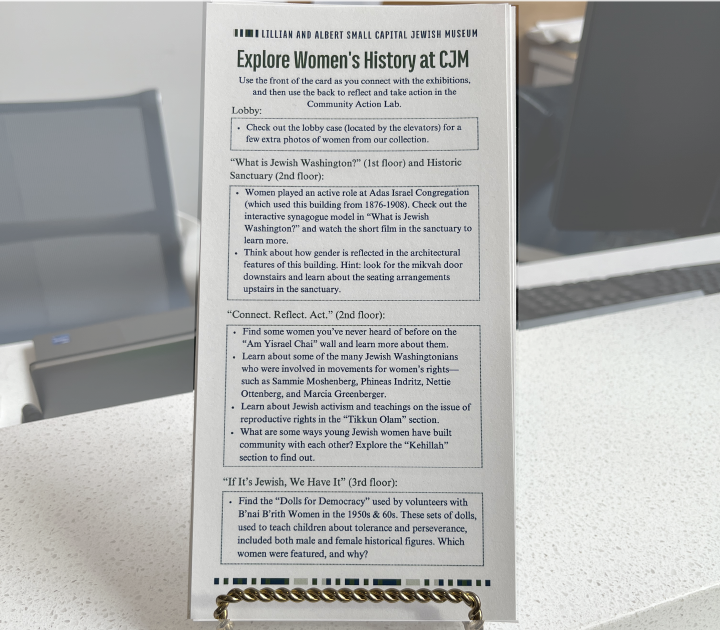

A short gallery guide for Women's History Month, available at the Cathy Bernard Welcome Desk.

Lobby case, Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum, March 2024. Photo courtesy of the Museum.

Our curatorial and education teams developed a short gallery guide, available at the Cathy Bernard Welcome Desk, that invites visitors to explore women’s stories throughout the exhibitions and provides some discussion questions.

Additionally, a rotating exhibition case in the lobby—one of my favorite features of our Museum—is themed for the month. We take the opportunity to note a problem with the limited data we have on some items in our collections: a plethora of unidentified women. Many of our entries—this is true of archives and museum catalogues around the country—list men’s names in the database followed by: “…and unidentified woman.” Who were these women and what are their stories? In most cases, we will never know. We selected some of these photos, added a pair of Shabbat candlesticks once lit by…whom? Also included are recipes in Sisterhood cookbooks attributed only to “Anonymous.” This case highlights the ways in which even these unidentified women are part of our collective story.

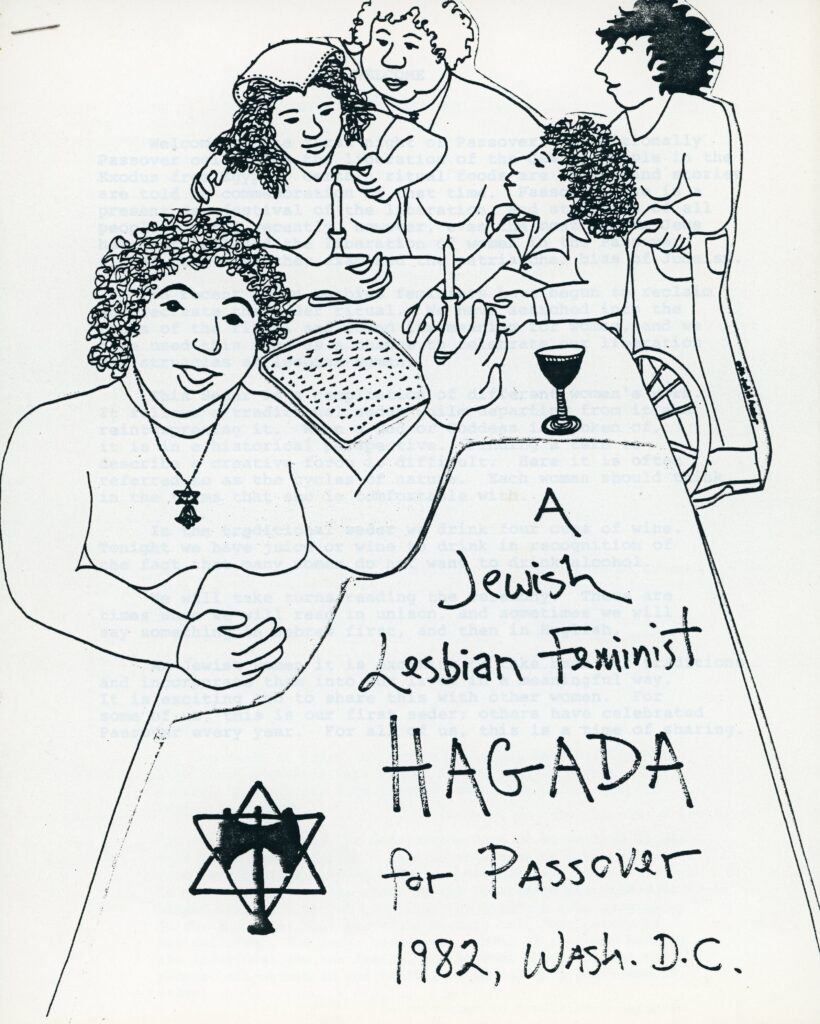

"A Jewish Lesbian Feminist Hagada for Passover," 1982. Capital Jewish Museum Collection. Gift of Susan Hester in memory of Mary-Helen Mautner.

Though our collection enables us to tell some selected stories of Jews of many sexual and gender identifications, we are always seeking new materials that will widen our scope even more. This month, a new acquisition in the CJM archives reminds us that our collection continues to grow. This Haggadah, a booklet of readings for the ceremonial Passover Seder, from the early 1980s includes new readings and prayers that help document the changes in Passover rituals over the 20th century, changes that will continue to expand in the 21st.

So how are we doing, as historians and museum curators in terms of making sure women are part of the stories we tell? In general, I think the state of the field in that regard is good and only getting better. But it’s always interesting to take the opportunity that Women’s History Month offers us to do some inward-facing work and strive to do better, being reflective about our own assumptions. What does it mean to claim to study the history of all genders?

View from the women's balcony inside the historic 1876 Adas Israel synagogue, ca. 1975. Capital Jewish Museum Collection

Mrs. Pearl Kipnis standing at the site of the mikvah built into the lower ground floor of the original Adas Israel synagogue on 6th and G Streets, NW, 1969. Capital Jewish Museum Collection.

In fact, gender is inscribed throughout the building itself: the Capital Jewish Museum is built around a historic synagogue, built in 1876 as Adas Israel Congregation. When the building was used as a synagogue, from 1876 through 1908, men and women were separated not only by tradition and worship practice but also by architectural features. Women sat upstairs on two balconies overlooking the main sanctuary.

Below the sanctuary was the mikvah, or ritual bath. Though men, and, today in some communities, non-binary people, can and do use the mikvah for certain ceremonial reasons, in the late nineteenth century, the regular monthly users would have been women. The door to the mikvah is all that remains today.

In 1969, when the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington banded supporters together to save and move the historic synagogue, Pearl Kipnis (1878-1976), age 91, visited the site of the old mikvah with her daughters Anne and Dorothy. Pearl was a Ukrainian immigrant to DC, while most of her family remained in Europe. This photograph is one of my personal favorites in the collection because Pearl stands so resolutely in a women’s space that is no longer a women’s space. Soon after this picture was taken, the historic synagogue would be moved down the street, and the mikvah would be left behind to the construction site. For the most part, my interest is in opening all our buildings and making them inclusive and accessible to all. But this Women’s History Month, it’s instructive to think about how women’s spaces have been and continue to be precious to many people.

For just this one moment, ahead of the wrecking ball, Pearl has reclaimed this space as her own.