The Whole Spiel

Ten Categories of LGBTQ+ Jewish Figures in DC History

by Sarah Leavitt, Curator

May 17, 2025

Washington, DC has long been a hub of activism, art, and identity—and LGBTQ+ Jewish individuals have played a vital role in shaping that history. This article highlights ten figures and community members whose contributions span law, culture, protest, and preservation, offering a glimpse into the rich intersection of queer and Jewish life in the nation’s capital.

- Lawyers. Who was it who said, ”First, kill all the lawyers”? But Shakespeare didn’t have to worry about anti-gay discrimination, at least as far as we know. Local Jewish lawyers who made real progress on LGBTQ+ rights include Roberta Kaplan, who argued a case for civil marriage; Barrett Brick, who added anti-gay violence to the State Department’s annual human rights report, and Susan Silber, who defended custody rights for gay parents. Don’t make me list all the Jewish lawyers, we’ll be here all night. The point is, it turns out Shakespeare was wrong on this one. We need the lawyers very much alive.

- Home Cooks. Movements need professionals but they also need random people on the street. And those people need to eat. One of my favorite food/protest stories is the member of Bet Mishpachah (DC’s LGBTQ+-friendly synagogue) who was caught on film at a Capital Pride parade in the 1970s handing out warm squares of noodle kugel on napkins to hungry people wearing rainbow mesh. Nothing says “finger food” like room-temperature kugel oozing with cottage cheese.

- Poets and Musicians. Ginny Berson and the rest of her Furies Collective made an impact on the lesbian arts movement with their Furies journal as well as her subsequent record label, Olivia Records, a tribute to the importance of music to 1970s lesbian culture.

- Innovative Activists. One popular form of 1970s protest was the “zap”–a moment of electrical energy inserted into regular life, such as the time in 1971 when activists protested the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in DC because of the inclusion of homosexuality in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. And they got it done! With the help of lots of other people, including local psychiatrist Stuart Sotsky, and probably a few lawyers.

- Angry Activists. Mattilda Bernstein might win the prize on this one—a trans Jewish woman who grew up in Montgomery County and used a suburban house on fire to illustrate the cover of one of her books. Her experience being bullied, abused, and misunderstood as a queer teenager led her to describe DC as “one of the most horrible places in the world without a question.” She did later come back to the area to join a protest march.

- Ally Activists. In any civil rights movement, allies are part of the story for getting things done, working the sidelines, and—in this case—recording the movement for posterity. Cheryl Spector became an LGBTQ+ activist after her brother’s HIV diagnosis in 1985. She worked with local organizations and also videotaped gay pride marches and other events, a wonderful way to capture this history.

- Posthumous Icons. Leonard Matlovich’s tombstone at DC’s Congressional Cemetery became a pilgrimage spot for gay activists. The decorated veteran was not Jewish, but he meant for this site to be a memorial to all gay veterans. The memorial usually has a pile of stones on top, a traditional Jewish way to pay respect to the dead.

- Phrasemakers. Blessed are the phrasemakers, for otherwise how would we move through the world so pithily. Frank Kameny coined the term “Gay is Good,” and it might not be in heavy rotation anymore, but certainly at the time it turned the conversation around in important ways.

- Photographers. Without the photographers, we would be far further in the dark about our common humanity. Most people, as it turns out, are not that great art photography, but even a snapshot helps historians and curators tell stories and build community with visitors. Art photographers, such as Jewish Washingtonian and famed lesbian photographer Joan E. Biren, bring us even closer into worlds, relationships, and historical moments we didn’t have a chance to see on our own.

- Historians. I’m one myself, so I suppose I’m biased here, but without the historians we have no museum exhibitions, no books, and no collective understanding of the past. It’s true that for decades—centuries—the world’s historians have ignored, cast aside, and otherwise sidelined LGBTQ+ history. In many ways this exhibition is a thank you note to the historians who stopped and listened; who edited anthologies (I’m looking at you, Evelyn Beck—Nice Jewish Girls, 1982) and who made sure that the record will show that learning the history of queer America, and all the activists, cooks, musicians, and lawyers among them, is right up there with Shakespeare, a fundamental reading list for all of us.

Visit the Capital Jewish Museum’s exhibition on LGBTQ+ Jewish history to learn these stories and more.

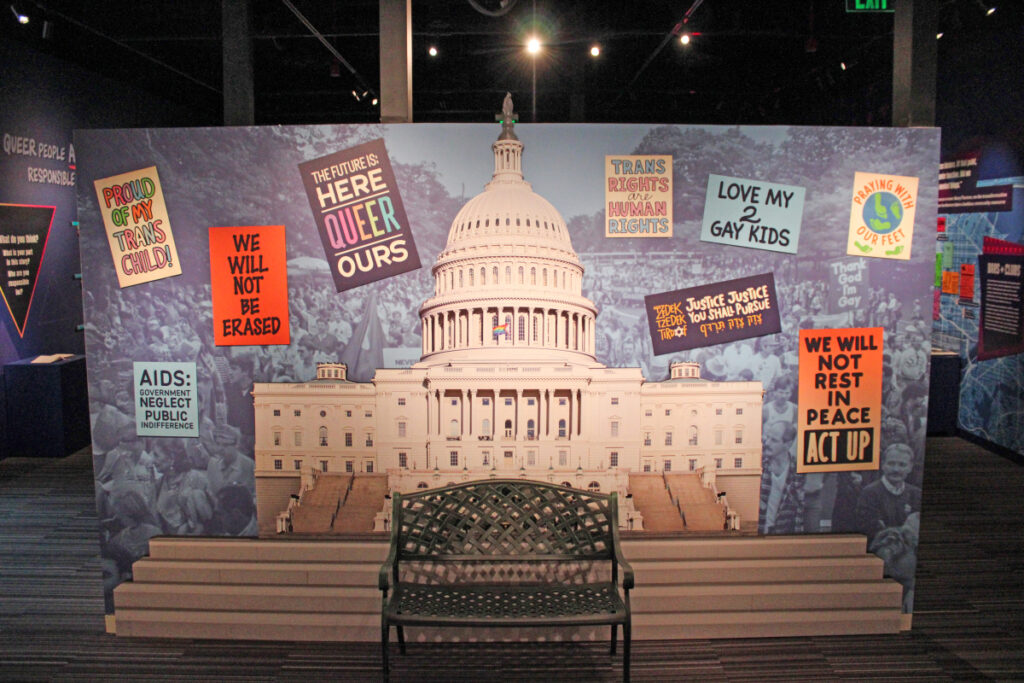

Gallery photo featuring a large-scale photo mural of the capitol building and a selection of protest signs from the Collection.