The Whole Spiel

A Fishy Story

by Sarah Leavitt, Curator

May 5, 2022

After two years of Zoom Passover, it was a delight to gather—after double-boosting and rapid-testing—for a family Seder (traditional ceremonial dinner). What was I most excited about, though? That this year, my mom would be in town to deal with the fish heads.

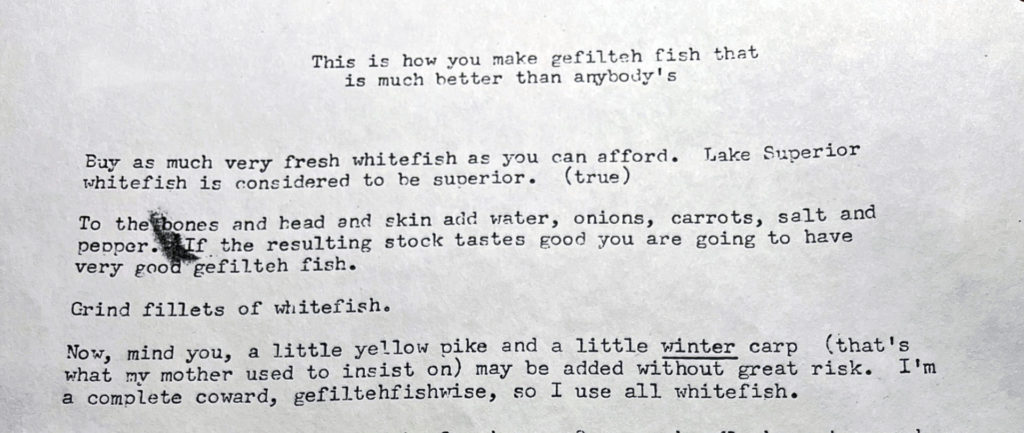

Detail of Sally Walzer's letter with recipe to her daughter, c. 1974. Photo courtesy of the Leavitt family.

Every year, my family reads aloud my grandmother’s 50-year-old typed-out recipe for gefilte fish, entitled “This is how you make gefilteh fish that is much better than anybody’s.” (What can I tell you, she was right). The recipe is not that hard—make fish broth, grind fish with matzo meal and eggs, boil fish balls, refrigerate—but one is to be excused for thinking homemade gefilte fish (not everybody’s cup of tea, after all) is a bridge too far on an extremely kitchen-work-heavy holiday.

I get that, of course, but to me, gefilte fish is the holiday. This year we eschewed matzo ball soup but made extra fish balls. However, the recipe gets dicey for me, fish heads not being personal friends of mine. For the first two years of the pandemic, I exhibited extreme bravery and made the broth myself. Honestly, I don’t know how I did it, but these last two years have revealed unknown strengths in each of us. This year, my mom got on that airplane, and I rejoiced.

When I was growing up, my grandmother would visit for Passover and supervise the chopping (sorry, Grandma, I meant the chop chop chop chop chopping). As she got older, she would sit at the kitchen counter and instruct my mom on the correct quantities of matzo meal. This year, my mom pretended to be nonplussed by my total failure to buy matzo meal, and we added matzo ball mix instead. (See also: we had no matzo ball soup).

Judy Leavitt preparing gefilte fish, 2014. Photo courtesy of the Leavitt family.

Gefilte fish has been a quintessential Ashkenazi (Jews of German and Eastern European descent) holiday staple for centuries. Nosher tells us that the earliest recipe can be found in a 700-year-old German Catholic cookbook, but the dish seems to have been considered mostly Jewish by the Middle Ages. In the American context, anyone who wants this “delicacy” can find the jars year-round in the “international aisle” at grocery stores. Though my grandma never bought such a thing (Or did she? Certainly not in my presence) gefilte fish was first jarred for mass-production (how “mass” was this production, really?) sale by Jewish food companies such as Manischewitz in the 1940s.

At the Capital Jewish Museum our collection of cookbooks—mostly from local synagogue Sisterhoods—includes several DMV-family recipes for gefilte fish. They do not really differ all that much—basically, a fish ball is a fish ball. I’ve hosted seders in Silver Spring for two decades now, so I suppose my family recipe now has its own local shine. I know which Montgomery County fish mongers will get the “right” Lake Superior whitefish. One year, there was a whitefish shortage and we made them out of salmon and (don’t tell Grandma) they were delicious. My mom, ever the traditionalist (she always comments on how, in her day, they did the chopping by hand) said they were fine but didn’t taste like Passover. Everyone else just douses them in horseradish such that they probably didn’t even notice.

The Passover table is filled with symbolism, each item representing part of the ancient story of the Israelites’ exodus from slavery. Telling the story every year helps us understand the importance of generational memory and the vital role that re-telling our histories plays in our lives. My grandma has not been with us for twenty Passovers now, but she is always with us at the Seder with her recipe—as sharp, funny, and homey as a hug. My mom is in her 80s now and “let” me do most of the cooking, but you’d best believe she stood by the stove and stirred those fish heads. My grandmother’s recipe is half-a century old, sent as a love letter through the mail, to her daughter who had moved far away and her toddler granddaughter (me).

Sarah Leavitt preparing gefilte fish, during the pandemic, while being supervised by her mother via video chat, 2020. Photo courtesy of the Leavitt family.

This year, my son came home from college for the Seder, and as I watched my mom watch him devour her gefilte fish—her mother’s gefilte fish—her grandmother’s gefilte fish (minus the carp and extra boiling)—I imagined him someday in the future, struggling with the fish heads and remembering this night. We can’t know what happens next year—may we all be free: of this pandemic, of this war —we can’t know what happens after that. But this recipe did not die with my grandmother, and I can only hope it will not die with me. We are lucky to have reached this season, with tall expectations for bravery and tradition, and with this recipe mostly intact.

* All pull-quote interludes are quotes from a letter, Sally Walzer to her daughter Judy Leavitt, c.1974.