The Whole Spiel

Everyday Heroes

by Eric S. Yellin, Ph.D., Senior Curatorial Consultant, Associate Professor of History & American Studies, University of Richmond

October 6, 2021

This summer (2021), we lost a special advisor to the museum, Avi West, a generous and respected educator in the greater Washington Jewish community. I learned many lessons about Judaism and Jewish values from Avi in the few years I knew him, but one stands out. We were discussing how to tell the stories of Jews in the federal workforce, and Avi said, “This important new definition of secular yet sacred community service became linked to patriotism and later to tikkun olam [the Jewish social action call to ‘repair the world’]. It begins the history of local ‘everyday heroes.’”

Avi West, circa 2019. Copyright Washington Jewish Week

Washington’s Jewish community has always included federal workers. Postal worker Morris Cohen and government printer William Bass labored in downtown offices as the community established itself in the mid-19th-century. In the first half of the 20th century, Jewish economists, statisticians, lawyers, and office workers came to DC by the thousands. Federal offices provided Jewish women and men with career opportunities limited elsewhere by antisemitism and sexism. By 1956, more than one-third of Washington-area Jews were employed by the federal government.

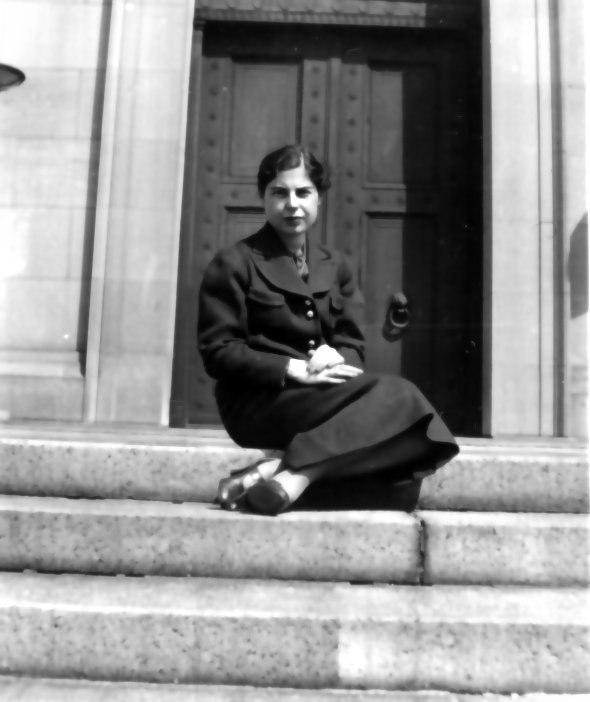

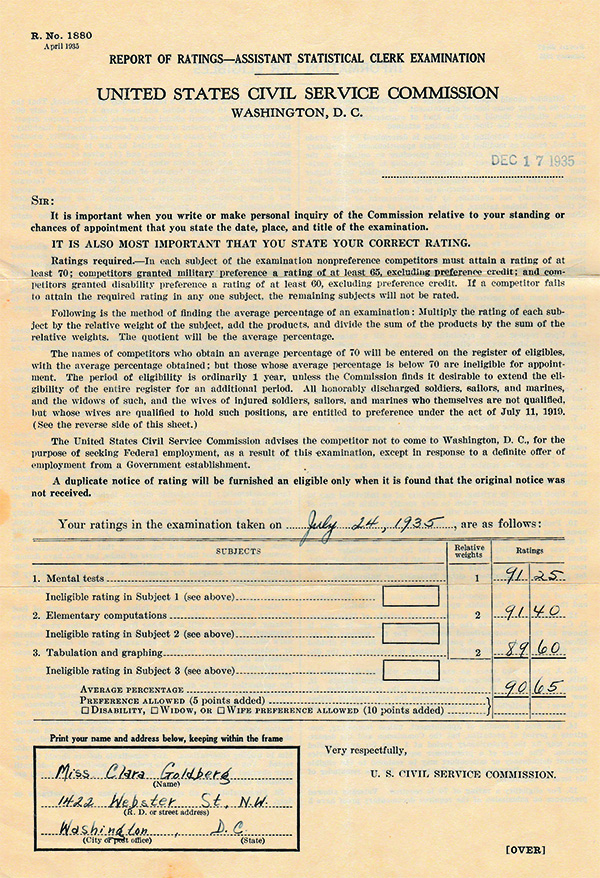

Clara Goldberg Schiffer was among them. Looking for work where she could use her education and considerable abilities after graduating from Radcliffe, she took the civil service exam. Her high scores landed her a job with the brand-new Social Security Administration. “I went to Washington in 1935, called from a Civil Service list, and was immediately plunged into a whirlwind of the New Deal,” she remembered. She wasn’t alone. One bigoted congressman accused the Social Security Board of hiring “too damned many New York Jews.”1 But for Schiffer (who was from Massachusetts), Social Security was an entry point into a 50-year career of “sacred community service” focused on poverty and public health.

Clara (Goldberg) Schiffer seated on the steps of a government office building, ca. 1935. Copyright Capital Jewish Museum.

When Avi called our attention to “everyday heroes” in Washington, he wanted us to focus on people other than members of congress, cabinet officials, and ambassadors. Schiffer never ran for office or held the ears of presidents. She studied, and she wrote. She commented on proposed legislation, testified before Congress, and drafted statistical reports. The work was never glamorous, but the impact on people’s welfare was real. The lives of domestic workers, mothers, children, elderly and incarcerated people were all made a bit safer and healthier because of her work. “I never lost the sense of excitement about the opportunity to use government to make the world a better place in which to live,” Schiffer said.

Clara (Goldberg)Schiffer's civil service application, July 1935. Courtesy of Schiffer family

So, what’s Jewish about this? Why bring up civil service on a blog for a Jewish museum? Avi taught me that Washington has been a place where generations of Jews have lived the rabbinic value of tikkun olam. To be sure, Jewish government workers, like others, come to DC for career opportunities – often it’s just a job, not a calling. But, Avi explained, it is the mitzvah (Jewish commandment) to heal the wounds of humanity that elevates the ordinary tasks of government work to something sacred and heroic.

Avi has been called a “master teacher.” This is one lesson the Capital Jewish Museum can pass along.

(1) Robert C. Lieberman, Shifting the Color Line: Race and the American Welfare State (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 73.