The Whole Spiel

Let’s Talk About Sex

by Sarah Leavitt, Curator

June 3, 2022

It’s probably not true that all museum curators think about sex all the time (at least not at work). However, if we’re doing our jobs right, certainly it is important to talk about sex, sometimes. (But only when appropriate, in case my boss is reading this).

As an avid museum visitor, I can probably count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen an exhibit that was explicitly about sex, and even those were not “explicit” in the delivery. (Though, I’ve not yet been to the Museum of Sex in New York). I’ve seen the National Museum of American History’s fabulous collection of birth control devices; I’ve seen plenty of nude paintings and sculptures; I’ve even visited the Dumas Brothel Museum in Butte, Montana and walked around the silhouettes of sex workers in the adjacent public park (sex work is work).

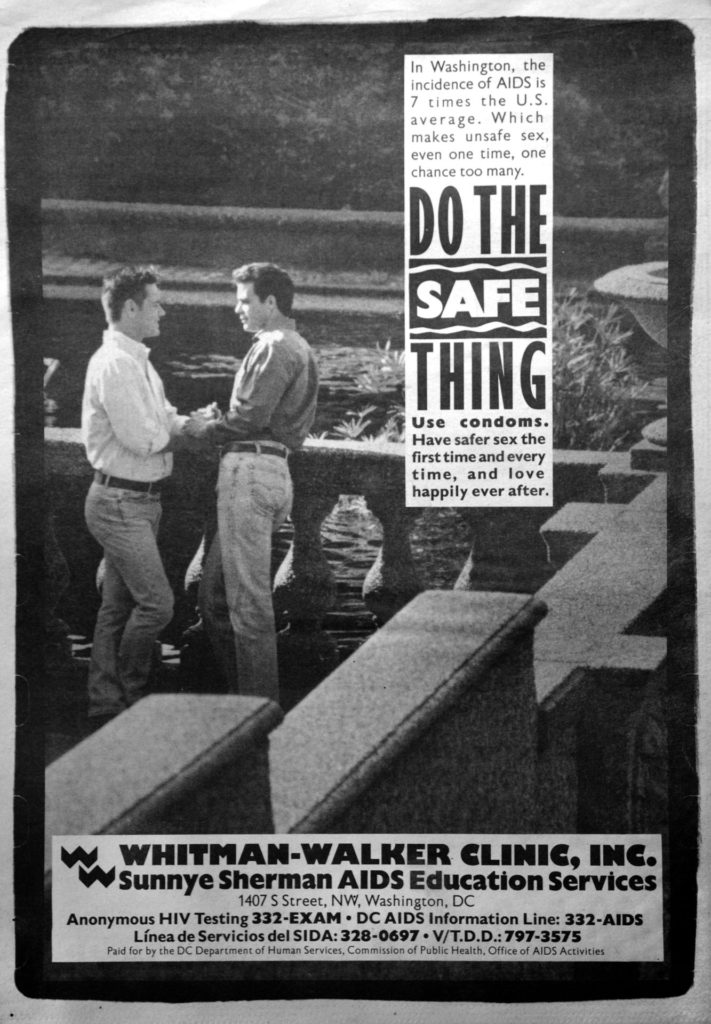

Promotional poster for Whitman-Walker Clinic's safe sex campaign featuring photography by Lloyd Wolf. Gift of Lloyd Wolf. Capital Jewish Museum collection.

As a curator, I’ve included sex in only a few exhibits. Many years back, I worked on an online exhibit for the National Institutes of Health about the history of the pregnancy test kit—a topic that is certainly sex-adjacent. In 2007, for an exhibition about domesticity and home life at the National Building Museum, we included a vibrator from the 1920s, a piece that looks like a power drill and, let’s say, gives many visitors pause.

Polar Cub Vibrator, ca 1920, from the National Building Museum exhibition House & Home (May 2012)

Still, I’m not quite an expert in terms of thinking about sex and museums (no, Ross & Rachel fans, I’m not talking about sex in museums). I do believe that history museum curators should be thinking more about sex, if we can figure out how to do so in a way that is helpful, rather than prurient. We talk about lots of other things that people do and experience—foodways, art, civic participation, school, worship, entertainment, work, and more—so, why do we shy away from sex? (Don’t answer that, it was rhetorical.) Young visitors, especially, need historical background to understand their world and the feelings they experience.

Which brings me to an upcoming exhibition at the Capital Jewish Museum, in which my colleagues and I are looking to tell the story of LBGTQ Jewish Washington. On the one hand, if we don’t talk about sex when we are doing history exhibitions about mostly straight people, why would we focus on sex when we talk about mostly gay people? But on the other hand, how can we talk about queer DC without talking about sex? How does the museum explain prejudice without talking about sex? And on yet another hand, can we talk about sex while remaining “family-friendly”?

CJM’s collection does not reveal much about the sex lives of Jewish Washingtonian, at least not yet. The largest relevant collection is a selection of posters promoting safe sex in the face of the AIDS epidemic, produced for the Whitman-Walker Clinic by the DC Department of Human Services. This campaign, dating from the early 1990s, features photography by Jewish Washingtonian Lloyd Wolf, though the posters themselves are not Jewish per se. Some of the posters use more explicit language about oral and anal sex; some use the more anodyne “do the safe thing.”

Our job now is to read some of our images and artifacts and find the stories of sex hiding within. (Don’t you do this at your job, too?). We have a corkscrew that reads “screw the patriarchy” on the side, a lobbying gift from the National Council on Jewish Women. It’s just a pun, but the object not only alludes to sex but to the NJCW’s work improving access to birth control. CJM has a collection of programs, menus, and fliers for young peoples’ matchmaking events such as dances at the Jewish Community Center or at local hotels. Surely, some of these dates led to sex. But predictably, that doesn’t usually come up in the oral history transcripts when older folks wax poetic about their younger years.

"Screw the Patriarchy" corkscrew given to members of Congress by members of National Council of Jewish Women lobbying on The Hill, 2020. Capital Jewish Museum Collection. Gift of National Council of Jewish Women.

Ultimately, I’m a built environment person, so I am always curious about where in the city things happen. Much has been written, in the historiography of gay America, about the ways that gay sex was hidden from public view in the past (and presumably in the present, too). Historians have documented (using various sources such as vice arrest records) sex taking place in parks—in DC, Lafayette Park right behind the White House was a place where gay men had sex in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. One diarist wrote in the 1920s about segregated areas at the park where Black men solicited attention, and Jewish men apparently had a “known” area, as well. So that’s something. Another place where historians have “found” gay men having sex is in the bathrooms at the YMCAs in cities across the country. These were all-male spaces without family oversight, so it makes sense. But in every secondary source I’ve read, historians only mention the YMCAs, not the YMHAs. Did Jewish men have sex at the YMHA? Presumably, sure. Is there a Jewish way to read this history? Can we look back at old photographs of the YMHA, established in 1918 on Pennsylvania Ave., NW, and imagine that the men who spent time there knew something about where gay sex was possible? The photographs cannot tell us, but they certainly raise questions. It seems likely that sex was among the activities that happened at the YMHA. Of course, many of these stories can never be told, and for the most part that is probably just as well. Maybe we are better off closing the door and leaving these stories at home (or at the Y).

Photograph of the buildings at the corner of 11th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. A large sign at the building on the left reads YMHA, 1920s. Gift of Jewish Community Center. Jewish Community Center Collection, Capital Jewish Museum collection.

But, where does that get us, in terms of how to talk about sex at the museum? Our curatorial team will keep thinking about how and when to openly talk about sex in our exhibits—whatever the theme. I think we want to keep imagining how to represent sex openly and with intention. Sex has a history, too, and it seems increasingly relevant to prepare our young people for open and honest conversations about sex—both in the past and in the present.

We are working to grow the collection to better reflect the communities we represent, including greater gender and racial diversity within our LGBQT+ Jewish stories. To discuss donations, please send an email to [email protected]