The Whole Spiel

Restoring Sacred Spaces

by Sarah Leavitt, Curator

December 19, 2024

On December 8th, five years since the devastating fire overtook the 12th-century cathedral in April 2019, visitors and residents in Paris got a special treat, just in time for the holiday season: the grand cathedral Notre-Dame reopened, in all (some might even say more than) its former glory. I would not recommend googling “fire + house of worship” like I just did—apparently just in the last weeks, several churches have burned down. According to the US Fire Administration, almost 200 houses of worship per year experience arson. And of course, as I write this, we have just heard the heartbreaking news of the antisemitic act of arson at Adas Israel synagogue in Melbourne, Australia.

Aren’t you glad you started reading this blog post? What I actually wanted to talk about is this restoration of a historic house of worship. At the Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum, we are ourselves custodians of such a place, a structure that was built as Adas Israel Congregation in 1876.

The historic synagogue is a baby compared to Notre-Dame. (construction began for the cathedral in 1123, but what’s a mere 753 years among friends?) And yet these stories are connected. In both examples, a religious space meant so much to the people of Washington, DC, and Paris (none of whom were alive to see their respective buildings constructed, but all of whom believed in their sacred importance) that they came together, spending a lot of time and money to preserve them for future generations to enjoy.

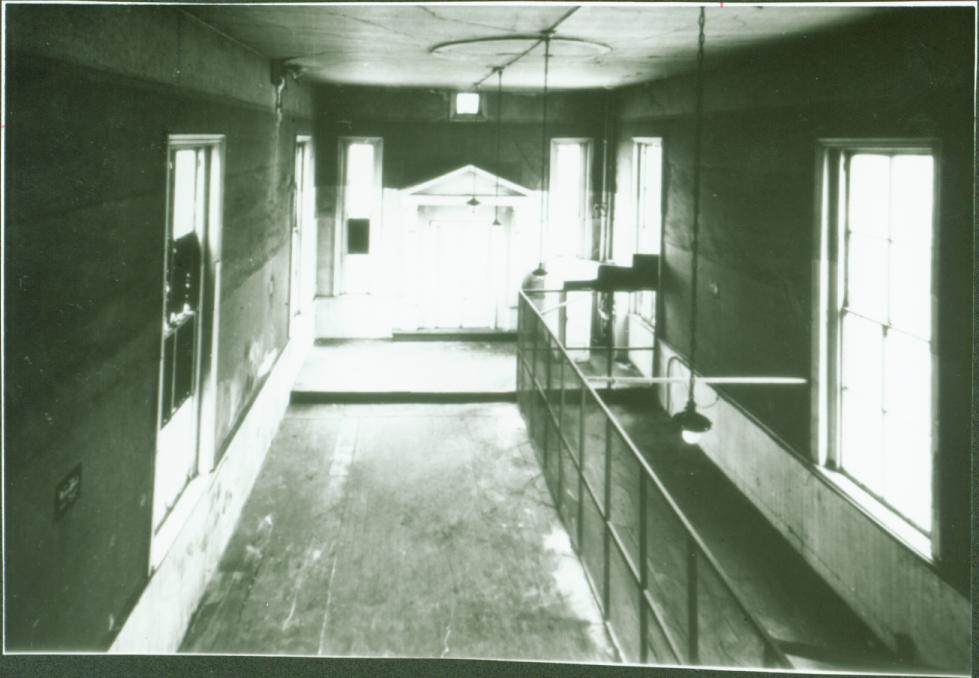

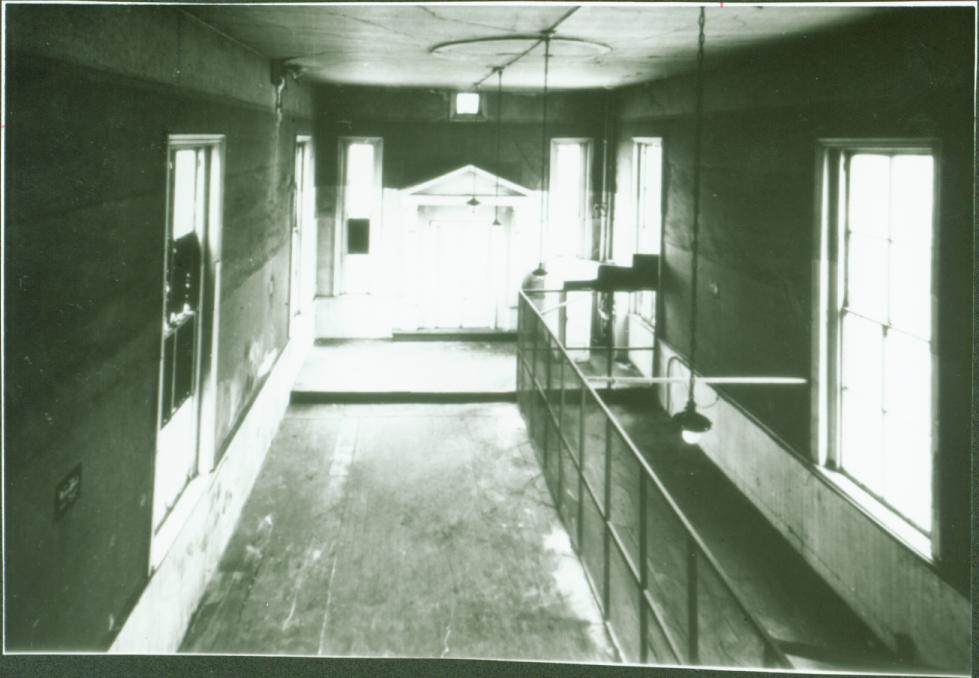

Black and white photograph of the interior of the historic synagogue building before restoration, 1969-73. Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum Collection.

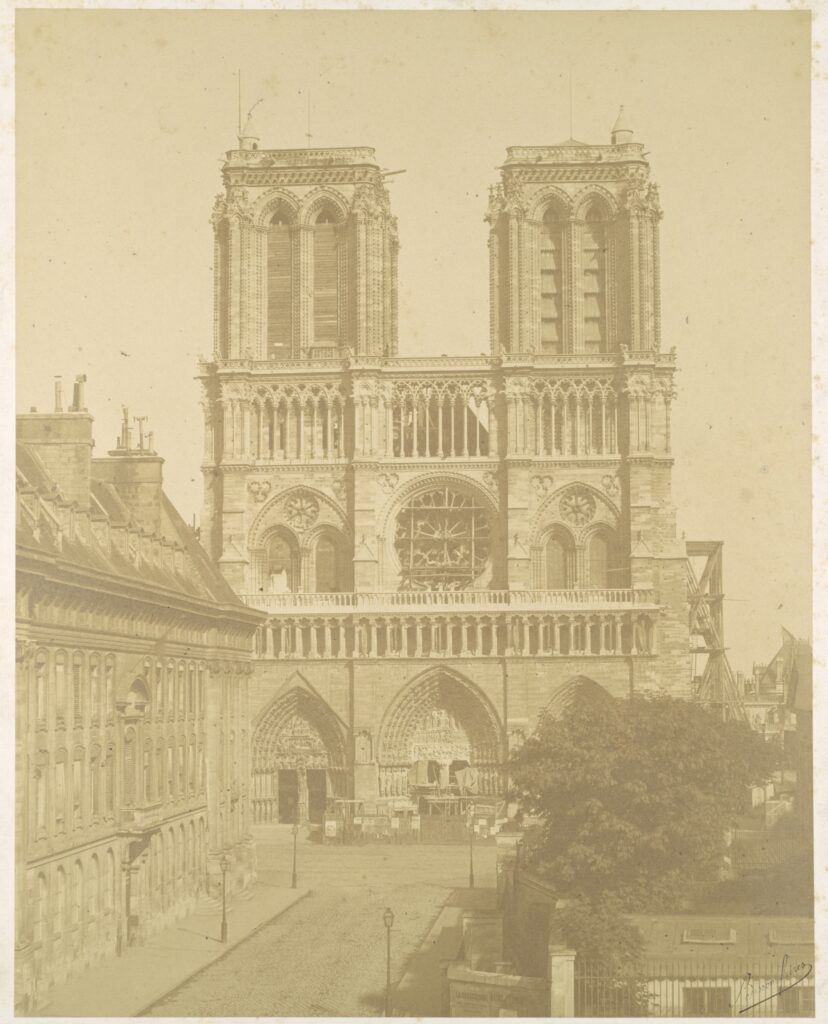

Black and white photo of Notre Dame cathedral, 1850s, by Louis-Auguste Bisson (1814–1876). From the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Notre-Dame

The architectural marvel that is Notre-Dame has been under almost continual construction and renovation over a mind-boggling 900 years. Over that time—and using many generations of trees—artisan woodworkers, stained glass artists, specialized scaffolding experts, and cordists (people skilled in the tying of rope, yes, I looked that one up) among them, have devoted time to this project. The outpouring of labor from around the world set to work on this project is an outstanding example of historic preservation at its most thorough and complex.

Historic preservation can test the bounds of what might be considered reasonable levels of meticulous, painstaking work, like, for example, the effort to make sure each oak tree’s contours matches the historical examples they were set to replace. The work at Notre-Dame took 2,000 workers and a staggering 900 million dollars. But in a world on fire, metaphorically, it can be a salve to put one out. The New York Times explained it this way, and I felt it in my bones: this project demonstrates to a broken world that “calamities are surmountable.” Historic preservation, when it works, sends such a message of hope: that the beauty of the past is somehow still accessible to us.

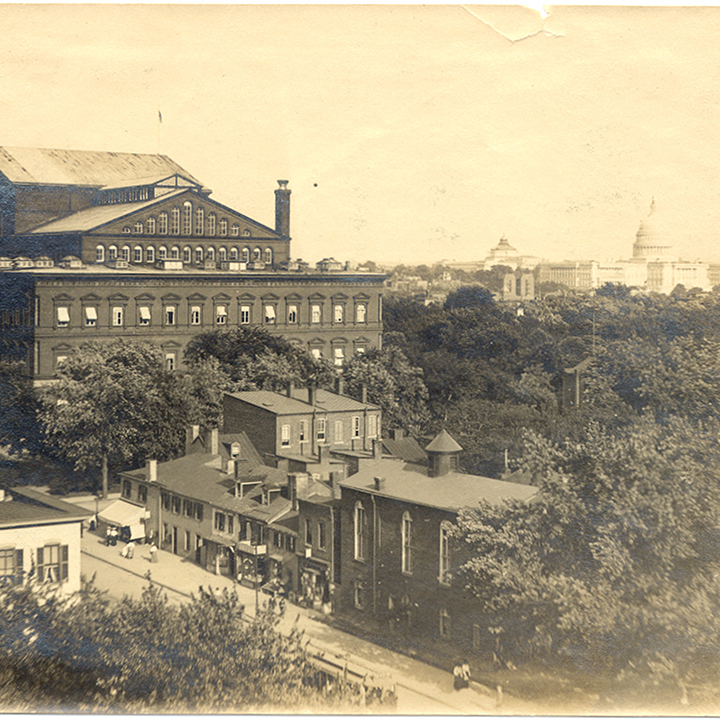

Historic Adas Israel synagogue (foreground) and National Building Museum, formerly the headquarters of the United States Pension Bureau, background, ca. 1905. Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum Collection.

Black and white photograph of the interior of the historic synagogue building before restoration, 1969-73. Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum Collection.

Adas Israel

In December 1968, a group of Jewish developers, their families, and others, began working together to save an old synagogue. That it was nowhere near as “grand” as Notre-Dame was immaterial to these budding preservationists. The simplicity of the building, its very humbleness, was part of the appeal. Many of these people, including Lillian and Albert Small, namesakes of our Museum, had relatives who belonged to the original congregation in the 1800s. The building was important to them for lots of reasons, some of them personal and others related to the interest in literally placing Jews on the map of DC. We were here, the restoration said. We helped build this city.

The winter of 1968 was a tough time for American cities, and it wasn’t obvious that there would be a growing, thriving Jewish population and Jewish museum in downtown DC 55 years later. Saving an old Jewish building in this neighborhood–in a period when the city’s Jews had largely moved to predominantly white areas in upper Northwest or Montgomery County–was a vote of confidence in downtown DC that at the time was not perhaps an obvious choice.

The team prepared a nomination form for the National Register of Historic Properties that reveled in the fact that on the second floor of the small brick building, the “synagogue proper…has survived relatively intact.” The building had been sold in 1908, with the second floor being rented by various churches and then used as a storeroom. “The outstanding feature is the original Ark of the Law” which still survives today, as does the “small blue glass window,” noted by the report, though we are not sure whether that was part of the original structure. The synagogue was moved, and saved, and it is because of the foresight of those historic preservationists that the building is part of our museum today.

Historic Sanctuary, Summer 2023. Photo: Imagine Photography

The Power of Sacred Spaces

Our historic synagogue and Notre-Dame can both reach across the centuries, even at different scales. I remember visiting Notre-Dame amidst the throng of other hot, tired tourists and hundreds of children yearning to get out of line and have ice cream (or was that just my child?). Even though it was a structure built in honor of a religion I did not subscribe to, I was moved almost to tears. (The Cathedral that did bring me to tears was Sainte-Chapelle. Oy! Those windows!) The tourists who visit Notre-Dame every year do so for various reasons—some having to do with religious beliefs and many having to do with the power of beautiful art and architecture to elicit feelings of awe. I think sometimes awe can act like a glottal stop does in spoken language. It’s a forced pause that allows you to get outside of your head for a beat and change your perspective. Chasing that feeling of awe down the aisle of a holy place certainly opens us up to dramatic emotional responses we might not expect.

Working just a few floors up from the 1870s synagogue, I can attest that the historic sanctuary can have its awe-filled moments. I welcome you to take a break from planning your trip to Paris and come on over to see us. Sit on a pew—they’re all from a previous century and have hosted many who might have been searching for answers, just like you. Look up at that small blue window of unknown origin. Close your eyes and think about what it means, to sit in a room where both Jews and Christians have worshipped, on and off, for 150 years. Think about how so many others have sat in that room and found solace, over and over and over again, in all sorts of different ways.

If a building can provide that sense of peace for somebody, even some of the time, maybe some of the world’s calamities are surmountable after all.